Executive

20 years after the Bridge:

Copenhagen/Malmö Still Chasing The Ambition Of A European Powerhouse

By Carsten Steno

Expectations ran high when the Danish Crown Prince Frederik and Sweden’s Crown Princess Victoria officially opened the combined bridge and tunnel across the Oresund strait between Denmark and Sweden on 1 July 2000. Now Greater Copenhagen, Malmö and Lund, along with the large catchment area for these three cities, would merge into a great new European metropolis. Businesses across the Sound would bloom, and Copenhageners and South-Swedes would gain an identity of their own as citizens of the Oresund region.

As Jens Kramer Mikkelsen, then the mayor of Copenhagen, said of the 16-kilometre combined bridge and tunnel across the Sound: ”We are not building a bridge – we are building a thousand bridges.” But 20 years on, the reality is that it did not happen.

The Oresund region does not have anything close to the level of political awareness which it held back then. At the national level, the governments of Denmark and Sweden rarely discuss the Oresund region. Previous ideas about coordinating legislation on labour markets and taxation to promote integration have not been realised. Things are somewhat better at the regional and local level, but authorities here have a more limited mandate for making decisions. To the extent that some integration has taken place, this has been primarily driven by the market and the business sector. But while the vision of a merged conurbation across the Oresund remains a vision only, new initiatives are required to force the Oresund region back up high on the agenda of both politicians and businesses. This is what Nordic Business has found in a status check ahead of a jubilee that is sure to be celebrated with pomp and circumstance and lofty speeches.

Commuting has peaked

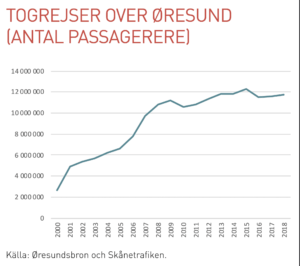

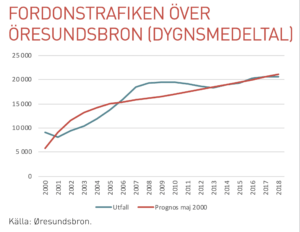

When it comes to visions and lofty words, it is always essential to look at the practicalities. Exactly how integrated is the region that comprises Greater Copenhagen, Malmö-Lund and the surrounding areas? The most easily measured factor is how the bridge is actually used. In 2000, when the bridge opened, just over 5,000 cars per day crossed the Oresund link.

In 2018, that number had increased to just over 20,000 – largely in line with the prognoses made in 2000 by the operator behind the Oresund link. The number of rail journeys across the bridge, which in the first year reached some 2 million, peaked in 2015 at 12 million, or some 32,800 individual journeys per day. Out of these passengers, about 18,500 were estimated to be daily commuters traveling across the Sound to work. In 2000, there were roughly 4,000 commuters, rising to a peak of 25,700 daily commuters in 2008 before dropping again, for a number of reasons.

Before the 2008 financial crisis, there was a substantial increase particularly in the number of Swedes gaining employment in Copenhagen. But since the financial crisis, the job market in the Oresund region has changed. Both sides of the Sound are seeing shortages of the same type of workforce. Another factor is that border checks have increased, extending the journey time to 35 minutes. These border checks were introduced in December 2015, initially in the form of ID checks at the Copenhagen Airport station at Kastrup, and later with spot checks on the Swedish side. Towards the end of 2019, Denmark introduced additional random ”crime checks” on the Danish side of the bridge crossing.

Danes have also stopped moving to the Malmö/Lund area to live, reversing a significant trend before the financial crisis, when house prices in Copenhagen shot up, making the housing market in the South of Sweden far more attractive to Danes. Today, some 19,000 Danes live in the wider Skåne region in the South of Sweden, while about 12,000 Swedes live in Greater Copenhagen. Development driven by markets and businesses While integration, as measured in traffic numbers and commuters, first grew and then stalled following the financial crisis, there has been a marked increase in business integration across the region.

The Oresund Institute, which analyses the Oresund region on behalf of private organisations as well as local authorities, concluded in a 2018 survey that the proximity between Denmark and Skåne has prompted many Danish companies to set up Swedish subsidiaries in Skåne. Companies in Skåne now have some 453 Danish board directors and executives, about as many as there are in Danish companies in the Stockholm region, a much larger area by far. The Oresund region has seen a particularly strong development in the pharmaceutical sector where the five biggest companies reached a record total turnover of 171 billion Danish kroner in 2018. Skåne in particular has attracted more pharmaceutical companies since the bridge opened, dominated by Novo Nordisk, LEO Pharma, Baxter Gambro, Lundbeck and Coloplast.

Today, the Danish-Swedish life-science industry in the Oresund region comprises more than 350 companies with over 44,000 employees. The Danish-Swedish venture fund Sunstone has also become a major active investor in new start-ups in the region. And the number of patent applications from the area’s pharmaceutical companies set a new record in 2019, as did their exports. However, Søren Bregenholst from Novo Nordisk, who is chairman of the Medicon Valley Alliance, stated towards the end of 2019 that it would require greater strategic coordination between Denmark and Sweden – both at the corporate and political levels – to see the pharmaceutical industry in Medicon Valley expand further. One of the hoped-for drivers of regional integration across the Oresund that initially raised expectations the most, before the bridge was built, centred on the research and educational efforts across the seven universities that are based in the Oresund region. Initially, it was hoped that a larger Oresund University would emerge from these, but it never came to fruition. The most tangible expression of collaboration across the Sound within the research field has been the establishment of European Spallation Source, or ESS, a multi-disciplinary research facility based on the world’s brightest neutron source. It is aiming to start its user programme in 2023. ESS is a European Research Infrastructure Consortium with 13 member countries and research facilities being set up around the University of Lund, while its data centres are to be located in Copenhagen.

Since the bridge opened, the respective port authorities of Malmö and Copenhagen have also merged into one single operator, and Copenhagen Airport at Kastrup has seen a massive increase in traffic – not least due to the growing number of passengers from the South of Sweden. On the cultural front, there is also considerable collaboration between theatres, opera houses and museums across the Sound, although, as yet, there are no joint institutions pulling the strings together.

Why integration has stalled The futurologist Uffe Paludan, who has specialised in the Oresund region, points to a number of reasons why the region has not yet become what many hoped it would be:

• First, the Oresund crossing was initially conceived as an intercontinental infrastructure project linking Sweden and, in particular, the city of Gothenburg with the European continent. That project was largely driven by Per Gyllenhammer, then the CEO and chairman of Volvo, and could only be realised once Denmark had built the Great Belt Link between the islands of Zealand and Funen.

• The idea of the Oresund region originally came about as an extension to the intercontinental project but has not found major support among government institutions, and in the Swedish capital of Stockholm there has never been any real interest in developing Skåne which, by Swedish standards, has tended to be considered a ”fringe area”. • While not much was happening on the political side, the market took over, but the market-driven development has stalled since the financial crisis.

• Since then, Danish politicians have seen promoting the Oresund region as less attractive due to increased border checks and growing media attention on Malmö as a crime-ridden city plagued by immigration.

At the same time, political cooperation has been hampered by the decision to close down the so-called Oresund Committee in 2016. Among other things, this Committee served to manage large sums of European Union funds for so-called inter-regional projects which were beneficial to integration in the Oresund region. Today, inter-regional cooperation is held back by Sweden’s administrative regions having a bigger mandate to make decisions and raise taxes, while Denmark’s administrative regions now primarily deal only with the hospital sector. Since a change in Danish business regulations in 2018, the country’s regions are no longer allowed to fund and engage in efforts to promote business.

This is another factor which hampers cooperation across the Sound. A new metro line may inspire renewed optimism According to Paludan, new initiatives are therefore needed to boost the Oresund region. Hence, in 2016, the idea was born to establish a new metro line between Copenhagen and Malmö. The rationale behind the idea was regional but also driven by expectations of an increase in commercial cargo traffic moving across the Oresund rail link, once the so-called Femern tunnel between Denmark and Germany comes into operation around 2028. Such cargo traffic will put a brake on passenger rail travel. Also, a metro between Copenhagen and Malmö would bring the journey time down to a mere 20 minutes.

A stronger common job market is needed In total, the ”Greater Copenhagen” organisation now encompasses 88 municipalities and four regions. Yet it is still a work in progress. Since it was set up, two executive secretaries have had a go at running it before moving on to other jobs. And while the organisation is now getting a new Director with a mandate to speak on behalf of ”Greater Copenhagen”, it remains unclear whether this will change anything.

Johan Wessmann, Chief Executive of the Oresund Institute, thinks that political cooperation across the region is now going through a transitional phase of finding a more definite form through the ”Greater Copenhagen” organisation. Among other things, he has high hopes for a so-called labour market charter now being developed by the 88 municipalities participating in the ”Greater Copenhagen” collaboration. The purpose of this charter is to lobby decision-makers at the national level with an overarching vision of creating an integrated labour market across the entire Oresund region. Today, there are many barriers. For example, a U.S. scientist with residence and work permits for Denmark is currently not able to work in the South of Sweden, something that ”Greater Copenhagen” is seeking to change.

”Greater Copenhagen” also points to efforts to boost cooperation in vocational training as well as promoting STEM skills and access to STEM education. STEM is short for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics – all skills that are in short supply throughout the region. Johan Wessmann also supports the idea that a metro line between Copenhagen and Malmö would boost the region, while stressing that there is a tendency in Denmark to overlook the development going on in Malmö itself. In fact, the Swedish city has been attracting more skilled workers and more financially strong tax payers, as demonstrated by the wealth of new housing projects which have sprung up on the Malmö harbour front. Helle Ahlenius Pallesen, who is Chief Executive of Oresundsadvokater, a network which offers legal assistance to companies and individuals in the region, is even clearer in expressing her view. ”We need a positive boost. I think it needs to come from all the many large companies in these regions which are looking for skilled labour. That can happen by making the labour market work better across the Sound, for instance. They need to demand that politicians make it happen by passing the necessary legislative changes

or coming up with new arrangements. That would create renewed optimism in the region,” says Helle Pallesen – who, by the way,

lives in Malmö but works in Copenhagen.