Sustainability

Companies Must Lead The Way In Sustainability

By Flemming Østergaard

Recently ECB, the European Central Bank, published some interesting research about finance and decarbonization. The findings in the working paper suggested that if a country wants to decarbonize its economy, it should not only promote green finance initiatives such as green bonds, but also develop its equity markets. Because economies that receive relatively more of their funding from stock markets than from credit markets generate lower carbon emissions per capita. Increasing the equity financing share to one-half globally would reduce aggregate per capita carbon emissions by about one-quarter of the Paris Agreement commitment, the researchers estimated.

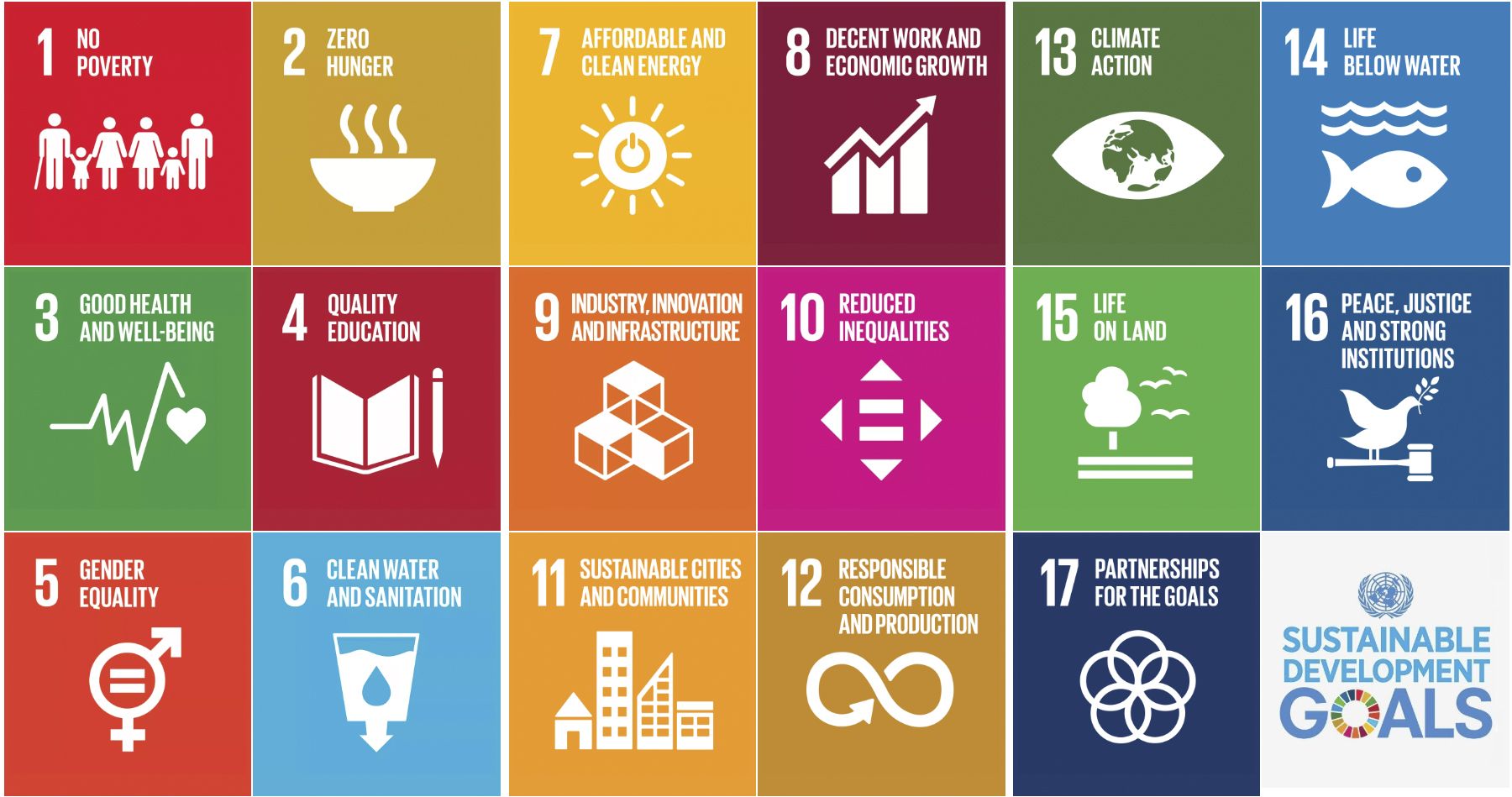

Carbon emissions are only part of the global agenda concerning sustainability. Many other environmental topics are in play, as well as social and governance matters. The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) and the 169 targets presented by the UN in 2015 can give you a good impression of many of the problems we are dealing with.

Highest ESG focus in Europe

In this transformation of the global economy companies play a very important role. So does the investment industry. In recent years we have seen a boom in the number of investment funds focusing on sustainability topics. And the public and political interest in the subject has never been higher – not least in Europe and the Nordic countries in particular.

An interesting report based on an extensive survey among 613 asset owners across the world, representing more than EUR 19 trillion in assets, was presented by UBS/Responsible Investor in 2019. One of the observations was that the highest proportion of asset owners already active in the ESG space exists in Europe (82%). European asset owners predict that systemic environmental factors (climate crisis, biodiversity loss) will be more material to their investments in the next five years than financial factors. The survey also revealed that a majority of asset owners claiming focus on ESG do actually walk the talk, when it comes to integrating ESG into the day-to-day work with their managers.

Nordea: The financial sector must lead the way

This is also the case at Nordea, the largest bank in the Nordic countries. The focus on sustainability is highly important in the investment processes. But it’s complicated, and common standards are lacking.

“It is difficult, and I think each sector needs to have their own legislation and full alignment to decide what’s the best possible option for that sector. But one thing that I think will be a very strong contribution going forward is now where we are seeing more legislation and also voluntary commitment in the financial sector. We’re connected to all sectors. So, if the financial industry as a central and key player starts to have tougher demands, both voluntarily and through legislations, then that will trickle down, and it will affect all our customers and all the companies we invest in. So, I think we need to lead the way, but it can’t just be up to the banking or financial services sector. The other sectors need to have their own specific targets,” says Anders Langworth, Head of Group Sustainable Finance at Nordea, the largest bank in the Nordic countries.

He further adds: “Looking a few years ahead, I hope, and I think, that we will stop talking about the sustainability options. And that every sector and our sector are setting more clear and precise targets to achieve, because it will never be possible to say that in 3, 5, or 8 years’ time, everything needs to be sustainable. We will still have fossil fuel, well, probably always a part of the energy mix. And then some people would say, well, that’s not sustainable. So, if we as a large bank are investing in 5000-6000 companies worldwide, we will have some investments in fossil fuels to some extent, most likely. And does that make us a completely unsustainable bank? I wouldn’t say so. No, not if we can show the transition and a decrease in those investments and significant increase in more sustainable options, and clear targets of what we want to deliver. And that is what I would like to see on a sector level. More clarity and hard facts of what we want to do – not just talk about ambitions.”

One of the problems of identifying and rating companies on their ESG efforts concerns the lack of data. Financial data is easy to get and is well defined by accounting standards, but that is not the case with ESG data. And even if companies declare to be ESG focused, it is often necessary to visit them to make deeper inquiries.

“The lack of data is the common problem for all sectors in our efforts to be able to really measure everything that we need to measure. We need to do a lot of company visits. Not just at HQ, our team also pays visits to factories or other parts of the company to really get a good impression of the company’s ESG efforts in practice. A company can write good reports about it, but we need to go out there in the field before we decide to lift the company into one of our sustainability funds,” says Anders Langworth.

Sustainable transitions take time

Hilde Jenssen is Head of Fundamental Equities at Nordea, a team consisting of 25 people located in Stockholm and Copenhagen, and is highly focused on the selection of stocks for the several specialized sustainability funds.

“We have a long-term perspective when looking at companies to invest in, our investment horizon is 3-5 years. And that is important, because a lot of the sustainability factors take a relatively long time to play themselves out,” Hilde Jenssen says.

She points out that another important part of Nordea’s approach to sustainable investments is to have a say in the companies, once the investments are made.

“We want to help push in the right direction, if you will – help businesses to improve their sustainable strategy, whether it’s about corporate practices, production methods, sourcing methods, or if it is connected to their social impact – something that has historically been important for our investments in emerging markets. However, social impact is also an interesting investment opportunity in developed markets, and we see a lot of interest from investors in this area.”

Find the winners when they are lagging behind

Bottom line is: The really interesting companies are not those who already have very high ESG ratings, but those who are on their way. Hilde Jenssen provides an example. Hawaiian Electric is a utility company based in – Hawaii. You would think that would be a perfect place for solar and wind energy. It is, but the company – that holds a monopoly position as an energy supplier for the entire group of Hawaiian Islands – has in fact imported petroleum in order to run their power plants.

“Due to their monopoly, they were not the fastest horse out of the barn to commit to the investments needed to make the transition. So, we engaged with the company and also teamed up with an activist value investor, who was also very much advocating for renewables. Together, we were able to work with the company to make the timeline much shorter for them to transition,” says Hilde Jenssen.

This example might give the impression that sustainable investing is an easy task, but that is definitely not the case, Hilde Jenssen points out. It is a world of shades of grey, and the lack of common standards makes it even harder.

“In each country in Europe, for instance, there is basically a different ESG label. If you have an ESG fund, and you want to market yourself in Belgium, then you would have to have the Belgian label. And if you are going into the German market, then you need the German label. The issue is that some of these labels have very conflicting views of the world. So, for instance, in Germany, they will exclude nuclear, however the French push for nuclear as a way to produce energy without any CO2 emissions. As a result, it puts an asset manager in a difficult situation, when you have to navigate among these conflicting country labels. What I’m hoping for is that we will move towards one standard. But I’m also realistic. I think, given each specific country’s political and strong commercial interests in this, it’s going to be very, very difficult to have one label covering all of Europe. That’s what we’re dealing with. But I do think there will be some extent of consolidation among these labels. The first sign of this we saw in December, when the EU reached a deal to define sustainable investments. A final taxonomy is currently expected at the end of 2021 with implementation in 2022,” Hilde Jenssen says.

Get inspired

Not every company is listed, quite the opposite, actually – most companies are not listed on stock exchanges. Obviously, this does not mean that unlisted companies cannot learn from large cap listed companies with successful strategies or banks’ ESG valuation methods.

The large companies are those who have the greatest resources for employing ambitious ESG strategies. And SMEs, listed or unlisted, should find inspiration here. Imitate what works to the extent it is possible in your company. Or as the famous composer Igor Stravinsky allegedly once said: A good composer does not imitate. He steals.